Adaptive Immune System Activation

Our immune system is one of the nature’s marvelous inventions and compels us to study its intricacies. Let’s zoom in on one of its details - the activation of the adaptive system. Keep in mind that the description below is subject to simplifications.

Innate system - the first line of defence

Whenever a pathogen (aka unwanted matter) enters our organism, the innate immune system is activated. One of its goals is to quickly remove any intruders and help withhold the homeostatis - balanced functioning of our body.

The innate system handles most of the simple intrusions but gets overwhelmed by serious adversaries such as the common flu or COVID-19. In order to overcome such encounters, it needs the help of the adaptive immune system.

Gathering intel

Throughout our bodies special cells are stationed - the Dendritic Cells. They continuously monitor their surroundings by sampling the matter around them, searching for anomalies. Most of the surrounding matter is considered “safe”. Those are remainders of dead cells, proteins etc. However, once a pathogen is found, the Dendritic Cell stops further sampling and embarks on a journey. It travels via the lymphatic vessels to the lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are staging points for the adaptive system and having reached them, the Dendritic Cell unleashes the full might of the immune system. An activation of the adaptive system takes place.

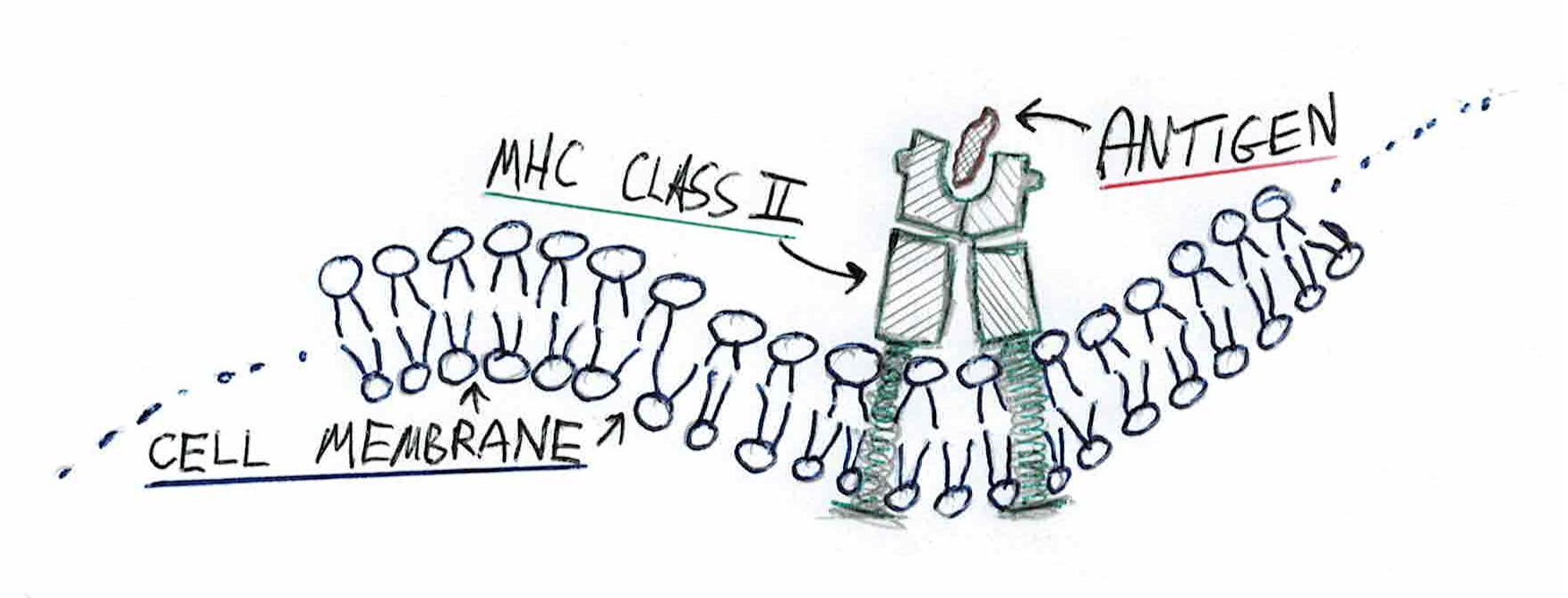

How does the activation work? Dendritic Cells are antigen-presenting cells. It means they express antigens on their surface. The extracellular antigens (those found outside of cells) are held on small protrusions on their membrane called MHC Class II. The abbreviation stands for the Major Histocompatibility Complex and, understandably, nobody uses the full name. A model of the antigen presentation is shown below:

A close-up on MHC Class II

After the pathogen is detected and displayed, the Dendritic Cell has to stop searching for new antigens. The journey to the lymph node may take many hours and stopping the scan ensures that the cell presents a snapshot of what’s present in the infection place. Notice how it means that the adaptive system takes some time before being activated. This is by design. The adaptive system is very costly for the organism and it would be counterproductive to activate it immediately. In the scenarios where the innate system can handle the infection by itself, the adaptive system might never be informed about the intrusion.

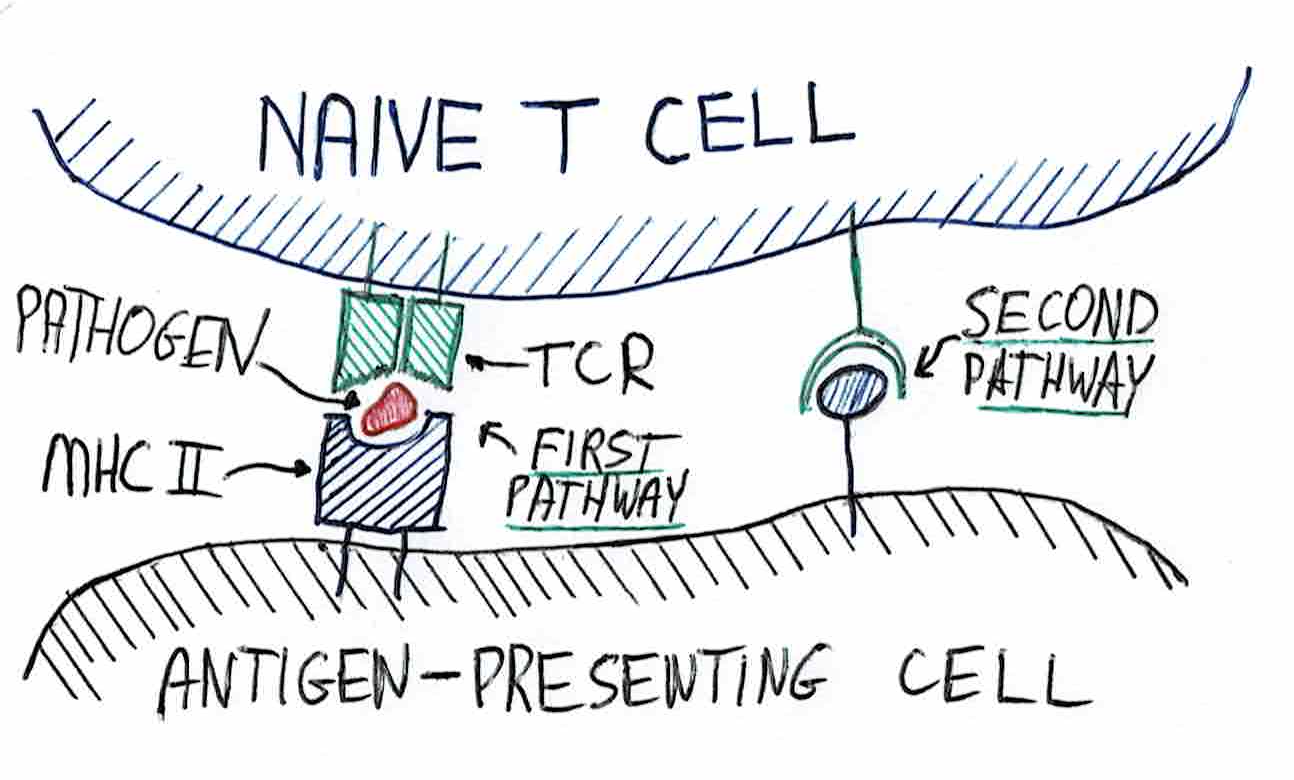

Having reached the lymph node, the Dendritic Cell encounters representatives of the adaptive immune system - the T Cells. Now, the T Cells are specific. Every cell is slightly different and able to recognize a specific pathogen. The T Cell will only recognize the pathogen it is able to effectively fight against. Therefore, the Dendritic Cell will “rub itself” against multiple T Cells until a match is found.

On the surface of the T Cells are receptors called TCR (somewhat surprisingly, the name simply comes from the T Cell Receptor). Once found, the Dendritic Cell releases a second signal. Its goal is to greenlight the activation and further minimize the risk of erroneous activations. Such signals are called pathways. In software engineering terms, pathways are calls to the cell’s interface.

The matching T Cell recognizes the pathogen using its receptor and becomes activated. Up to this point the cell was classified as a Naive T Cell. It will now take new responsibilities. This specific process creates a Helper T Cell. Depending on the type of activation, other type of the T Cell might be created. Importantly, in the current case, the pathogen is extracellular. It comes from the outside of the cell. To help fight such an infection, the adaptive system will significantly boost the innate system’s defenses. Had it been an intracellular infection, the reaction would have been different.

Two pathways during T Cell activation

Having been activated, the Helper T Cell starts multiplying in the lymph node and split into two halves. One half heads towards the infection place. Its primary goal is to support the cells of the innate system. It grants permission to intensify the efforts even despite collateral damage done to the body. This is achieved by releasing molecules that stimulate the bactericidal behaviour of the innate system white cells. The other half continues to activate further cells of the adaptive system - the details of this process are skipped. The aid coming from the Helper T Cells may prove sufficient to overcome the disease. Healing however will take longer.

All cells have an internal clock that limits their lifespan. After several days almost all of the Helper T Cells die via process of apoptosis. This process means that a cell self-desintegrates and its innards can be recycled. Some of the T Cells, however, survive and remain in the body. Those cells constitute the acquired immunity against the disease or memory thereof. The existence of those memory cells greatly expedites the immune system reaction against the next infections caused by the same pathogens.