Mangroves

The Earth’s ecosystem offers a plethora of potential niches and some of the most extraordinary adaptations observed in organisms are a result of inhabiting the more extreme ones. One of such niches are tropical saline coasts populated by mangroves.

A mangrove tree of Rhizophora species

The niche comes with a set of problems that the mangroves evolved to solve. The habitat is regularily flooded with water level differences reaching over a meter. The soil itself is deficient in nutricients and oxygen. Mangroves solved this issue by growing a specialized type of roots above the surface of mud and water and gathering oxygen directly from the atmosphere with them. Due to oscillating sea level, these roots must protrude significantly from the soil. Such roots are called pneumatophores (ancient greek: pneûma - air/breath, phérō - to bring).

There are two ways of envolving roots to stretch into the air. They can either:

- extrude from higher up the tree’s trunk

- return back up above the surface after growing in the soil

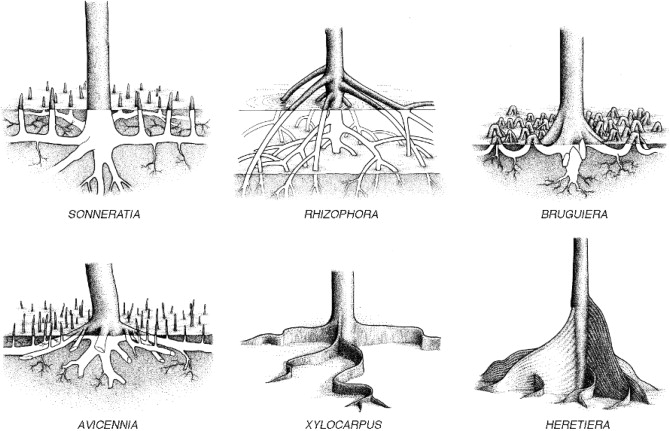

In an interesting example of the convergent evolution, different species of mangroves explored both of these options:

Root systems of common mangrove trees

The most iconic Rhizophora species grow aerial stilts from the trunk. Those serve as pneumatophores and, having reached beneath the surface, they branch into a set of anchoring roots. Notice how all of the species lack the strong tap root (a strong, dominant root. Think of carrots.). It is not needed in relatively dormant waters, devoid of strong waves and frees up the resources to invest in more intricate pheumatophore system. Instead of sprouting separate roots, the Xylocarpus and Heretiera have compressed, clustered roots stretching high above the surface instead.

The second approach is growing protrusions from below the soil. Notice how Sonneratia and Avicennia grow them directly from the root while Bruguiera extrudes the root itself - the same idea was implemented by two different adaptations that evolved independently.

Another problem to tackle is salt contents. The water salinity in mangrove area can be three times higher than in normal sea water, which is a 100 times more saline than most plants can survive. The plants solve this issue by:

- limiting the input - it is achieved by the structure of the roots, which filter out over 90% of salt in the sater intake.

- excreting excess salt - it is commontly done through the leaves. The salt forms crystals and is eventually washed or shaken away.

Salt crystals on the mangrove leaf

Finally, the mangroves evolved to be viviparous. It means that their seeds germinate attached to the parent tree and detach after they’ve formed a so-called propagule (a self-sufficient seedling that can conduct photosynthesis). The propagules are then dropped into the water and transported by the flow until it reaches a place to take root.

A seed growing on a tree, ready to detach

[Source: The Palm House, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen]

[Source: Friedhelm Göltenboth, Sabine Schoppe - Ecology of Insular Southeast Asia, Elsevier 2006, ISBN 9780444527394]

[Source: Wikimedia]